The elegant pithead baths built for Britain’s miners in the 1930s are among the country’s best examples of modernist architecture; technologically advanced and progressive they once stood as proud symbols of miners’ welfare. Yet despite their socio-historic and architectural importance they suffered badly following the decline of the coal industry; many have been demolished, while others continue to struggle to find a purpose in the communities they once served.

Traditional welfare provision for Britain’s army of miners (well over a million men at the beginning of the 20th century) was universally poor. Few miners were lucky enough to live close the colliery and many had to walk long distances before descending the mine, only to walk even further underground (in some cases several miles) to reach to the coal face. On finishing a shift the exhausted miners faced the long walk home in all weathers, their sweat and mine-water soaked clothes bringing with them the threat of pneumonia and bronchitis. Baths were taken outdoors in warmer weather but in the cooler months the tin bath was brought in front of the fire, bringing the soot and dirt of the mine into the domestic environment. Miners’ wives were subjected to the back-breaking work of a daily battle against coal dust and cleaning of the heavy work clothes and boots.

The establishment in 1926 of a special fund for pithead baths under the control of the Miners’ Welfare Committee (M.W.C.) was the culmination of decades of campaigning to improve facilities for miners. The committee derived its revenue from levies of halfpenny per ton of coal produced and one shilling in the pound on mining royalties, plus contributions taken from the miners’ own pay. Representatives of both coal-owners and mine workers sat on the main committee drawn from the 25 coal-mining area district committees.

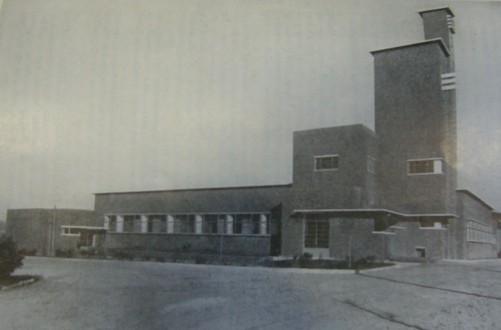

During the period 1921 to 1952 over 400 pithead baths were built under the direction of the M.W.C.’s regional architects departments. By the 1930s a distinctive Functionalist house style had emerged, which made use of glass to bring light into the baths and distinct interior zoning (clean room, dirty room, cafeteria, community centre etc), each zone reflected in the massing of the baths’ exterior. Square towers were common and built to house the large equipment required to provide hot water for showers and blow a constant stream of hot air through the lockers to dry off the miners’ dirty clothes.

©2017 Modernist Tourists

September 23, 2021 at 1:33 am

How many of these structures remain? Have any been repurposed or have they been demolished?

– Paul

LikeLike

September 23, 2021 at 2:18 am

Sorry, I forgot to add that I have a reference to Messrs. J.H. Forshaw & C.G. Kemp as the archietcts of the pithead baths and recreation centre, Betteshanger Colliery, Kent, 1934. In: David Dean “The Thirties: Recalling the English archietctural Scene” (1983), p60. I can email an image from the book.

Cheers -Paul

LikeLike